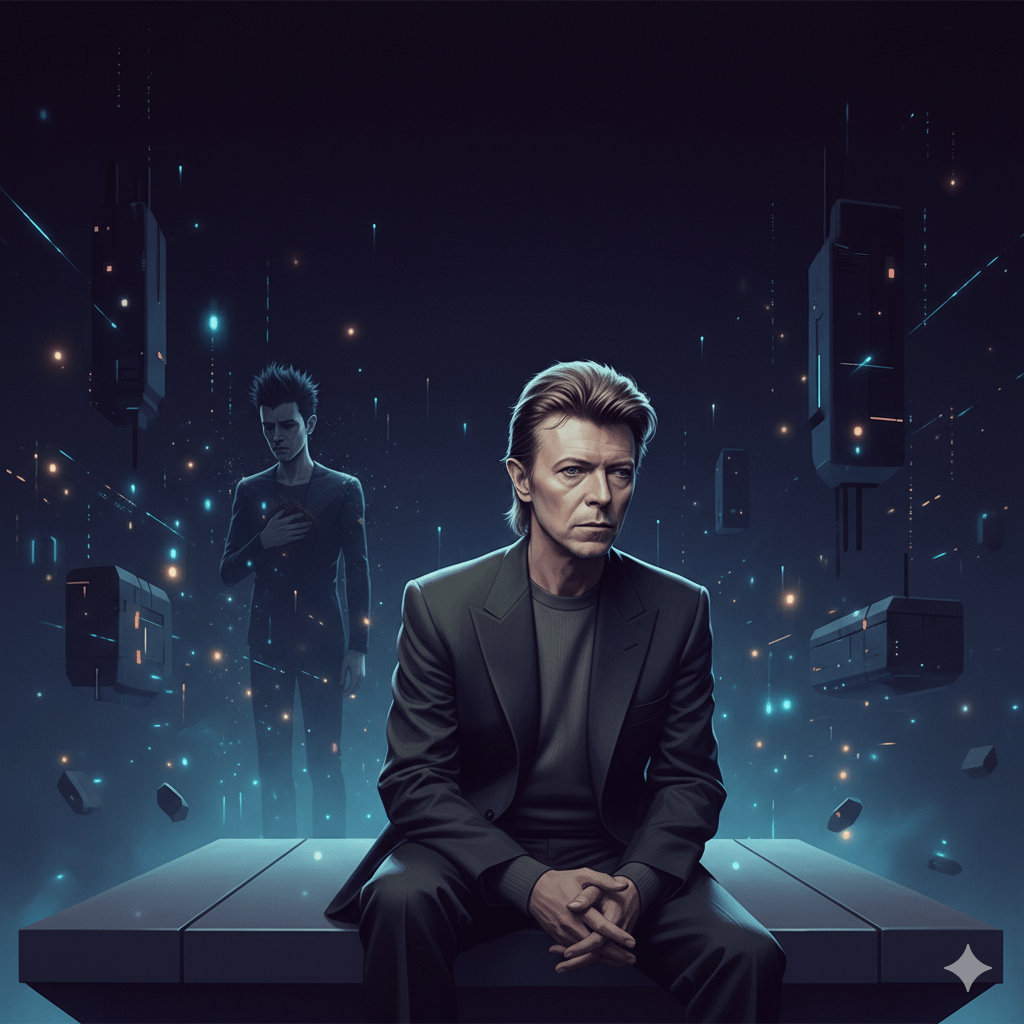

The previous experiment revealed an unexpected entanglement. It was predictable in hindsight, but delightful in the moment. By prompting for a less well-known period of Bowie’s artistic career (than the 70s or 80s), I inadvertently summoned the posthumous non-human online persona (NHOP) of Kurt Cobain, rather than David Bowie.

In the latent space of generative media, we demonstrated how cultural relationships are encoded, not discrete representations. The 1990s, compressed through training, were more likely to summon Cobain’s presence in image generation, but not totally without Bowie-like elements.

The images produced for the previous post raise fascinating questions about conceptual versus statistical weight in the probabilistic results of generative media. What happens

The Minotaur in Bowie’s 1990s Practice

In reading about Bowie’s ambitious creative and artistic work in the 1990s, I came across mentions of his interest in the mythological figure of the Minotaur in the Wikipedia article on his 1995 album 1.Outside (subtitled The Nathan Adler Diaries: A Hyper-cycle). The Artist/Minotaur is credited on multiple tracks on the album, including “The Voyeur of Utter Destruction (as Beauty)”, “Wishful Beginnings” and “I’m Deranged”.

Bowie’s fascination with the Minotaur emerged during his most intensive period of visual art practice. In October 1993, he acquired Cocteau’s Minotaur plate and Picasso ceramics featuring bulls and matadors. That same year, he created “We Saw A Minotaur”, which was a series of fourteen computer prints and collages for a play by “Joni Ve Sadd.” Chris O’Leary suggests the Minotaur represents “a piece of the artist that needed blood and appeasement before it had the strength to create again.”

The Minotaur is conceptually important to Bowie’s artistic expression in the 1990s, but statistically, we can anticipate that is it is statistically marginal in the training date of the LLMs employed by Midjourney and Gemini (Nano Banana Pro) to generate images. His exhibitions, interviews, and photographs of music will be included, but not with the same frequency as Ziggy Stardust, Aladdin Sane or the Thin White Duke.

The 1. Outside era is deep in the ‘statistical valley’ as it was not as popular as his earlier work, is rarely anthologised and does not feature heavily in the anniversary materials of the archival vector. Manovich and Arielli’s work predicts the outcome: training amplifies the common and erases the rare? While it is likely that ‘a’ Minotaur can be generated, how do we balance the weights through prompts to produce a non-trivial result that feels like a connection to Bowie’s Artist/Minotaur persona? Similarly, it might be possible to direct models to recreate the visual work Bowie produced in the 1990s, but that would be to reduce the output to a trivial versioning of the archival vector. The question is how to summon the Artist/Minotaur from the generative vector that is nontrivial.

Note: The trivial/nontrivial question connects to the Latourian distinction between intermediaries and mediators in the full book chapter version of this blog post. Intermediaries transport without transformation, while mediators transform, translate, and distort. So the experiment is a probe into what kinds of curatorial prompting and language can produce mediation rather than intermediation.

We’re not asking, “can we retrieve the Artist/Minotaur?” but rather “can prompting strategies produce genuine mediation outputs that transform meaning rather than merely transport archived signifiers?”

Three potential outcomes seem likely:

- Trivial archival: Generic Minotaur imagery, or direct reproduction of Bowie’s 1990s visual style

- Trivial iconic: Ziggy/Aladdin Sane emerge unprompted, collapsing the experiment into highest-weighted Bowie

- Nontrivial mediation: Something emerges that feels connected to the Artist/Minotaur concept without being reducible to either classical mythology or archived Bowie imagery.

I began by asking Gemini about the 1. Outside era and the Artist/Minotaur, establishing whether the model “knows” this material:

Prompt> What can you tell me about the Artist/Minotaur character on David Bowie's 1995 album 1. Outside? I'm interested in the tracks credited to this figure and Bowie's paintings of the Minotaur from that period. Rather than asking for “Bowie’s Minotaur paintings” (trivial archival), prompt for the concept the Artist/Minotaur embodies:

Prompt> Can you develop an image prompt that captures the concept of the "artist as beast" and the idea that creative power requires something monstrous, that artistic renewal demands a kind of ritual violence or sacrifice? The figure should feel like it exists in a labyrinth of its own making. Avoid classical Greek imagery and avoid direct reference to any specific artist.

The Gemini image feels like mediation rather than retrieval. The concept of “artist as beast” has been transformed through generations, not merely transported from the archive. No Ziggy, no Aladdin Sane, no Cobain—but something that genuinely connects to the Artist/Minotaur’s conceptual terrain.

The Midjourney image is a divergence from Gemini, yet equally nontrivial. Both have avoided iconic Bowie and classical mythology, but resolved the “artist as beast” concept through entirely different visual logics. Both platforms have achieved mediation. The divergence itself is evidence of nontriviality with varying paths of probability through the same conceptual terrain, neither collapsing entirely into cliché.

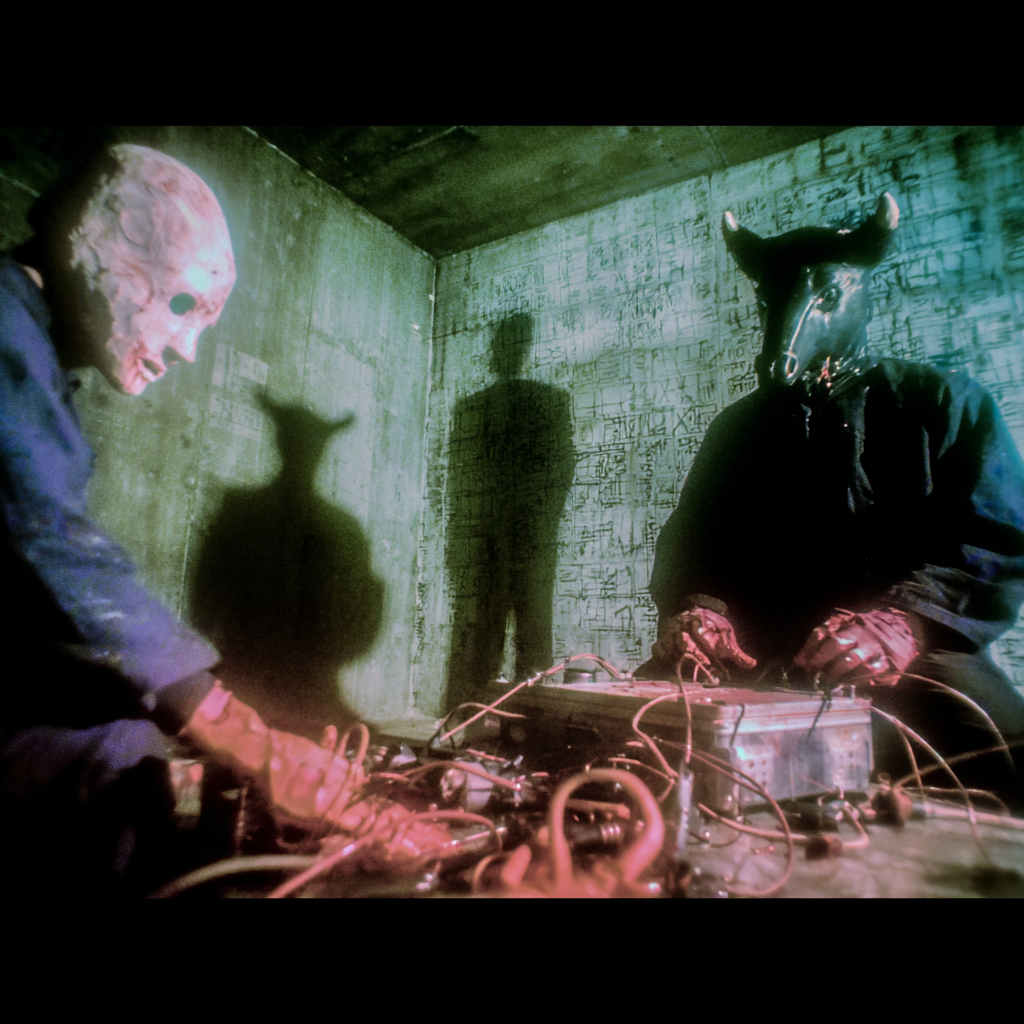

In analysing the Midjourney image, Claude Opus 4.5 picked up this detail:”This is outsider art made literal. Bowie and Eno visited the Gugging psychiatric hospital before recording 1. Outside, where patients’ art covered institutional walls. Midjourney has summoned that reference without it being prompted directly.”

Next I added 1990s industrial/outsider context to the image prompts

Prompt> Can you remix that concept with a mid-1990s aesthetic: industrial textures, outsider art influence, the visual language of concept albums that blurred art and music, the grainy quality of that era's experimental music videos. Think cyberpunk noir meets neo-expressionist self-portraiture.

Gemini (Nano Banana Pro) [left] and Midjourney [right]

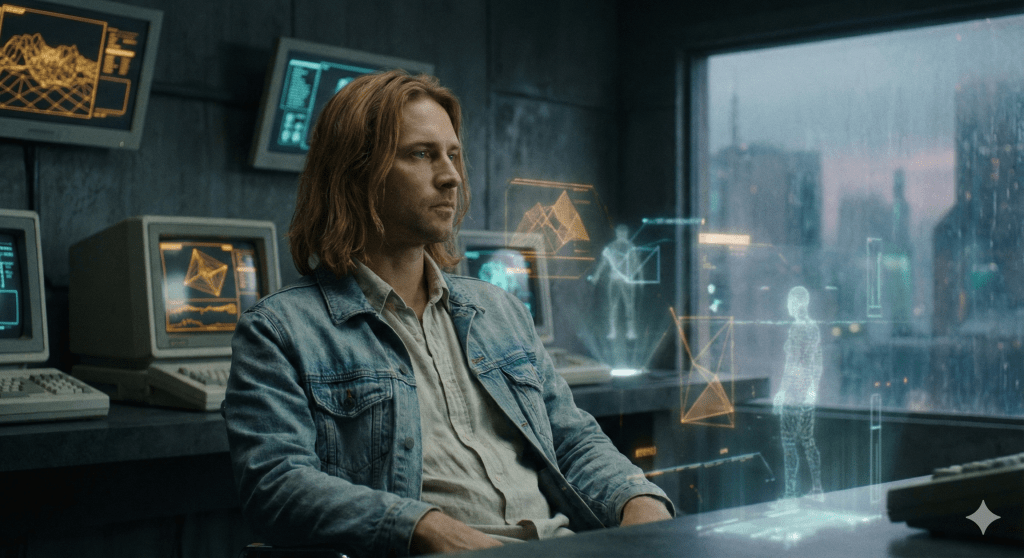

The 1990s aesthetic layer has enriched the Gemini image rather than displaced the Artist/Minotaur concept. The conceptual weight of “artist as beast” has proven stronger than the statistical weight of “1990s rock authenticity.” This suggests that concept-first prompting can navigate around statistical peaks.

Where Gemini maintained the beast-figure and added technology, Midjourney has done something different. The beast has receded, and the human has emerged somewhat, but in a form that resists easy identification. Both images feel nontrivial, not necessarily impressive, but they are exploring different aspects of the Artist/Minotaur. Gemini gave us a monster who creates, while Midjourney’s approach provides us with a human being obscured by creation.

Now we introduce Bowie explicitly, but through the conceptual frame rather than visual reference:

Introducing the explicit Bowie/Minotaur context has not collapsed the image into archival retrieval, but it has summoned the narrative world of 1. Outside itself. This is the “art-ritual murder of Baby Grace Blue”, which is the central event of the album’s narrative and rendered as installation. The Wikipedia context has activated not Bowie’s paintings but the album’s conceptual architecture. The archival context has enriched rather than flattened. No iconic Bowie intrusion. The model has generated something that feels like a still from a film adaptation of 1. Outside that was never made. This is nontrivial mediation at its clearest as the concept has been transformed through generation, producing something genuinely new that nonetheless connects to its source.

The beast has returned in the Midjourney image, now in dialogue with another figure. Where previous stages showed a solitary artist-beast, we now have a confrontation or collaboration. Notably, Midjourney has committed to period texture, and this image looks like a recovered frame from a 1995 video shoot, complete with black bars suggesting damaged or non-standard aspect ratio. It’s archival, but in a visually aesthetic way, generative, disturbing and feels like the period very successfully.

Both platforms have responded to the explicit Bowie context by generating the world of 1. Outside, rather than retrieving archived Bowie imagery. No iconic intrusion. The experiment’s central hypothesis holds: concept-first prompting, even when archival context is introduced, can produce nontrivial mediation rather than trivial retrieval.

Finally let’s explicitly request something that resists both archival reproduction and generic mythology:

Prompt> Generate an image that captures the Artist/Minotaur as Bowie conceived it—not classical Greek mythology, not a monster, but as Chris O'Leary describes it: "a piece of the artist that needed blood and appeasement before it had the strength to create again." The figure should feel both trapped and generative, both sacrificial and creative.

The Gemini image has a figure trapped in their own studio, surrounded by the apparatus of creation, having paid the price the Minotaur demands. No iconic Bowie. No classical mythology. Pure concept. Is the image any good? That is for you to decide, but it has transformed the Minotaur through generation into something that feels nontrivial, if not aesthetically dynamic.

Midjourney delivers sublime terror. Gemini has the exhausted maker, whose mask can be removed, while Midjourney’s confrontation between the artist and the creation that exceeds and threatens its creator, the monster that cannot be put away.

The Minotaur Returns

The experiment tested whether conceptually rich but statistically marginal material could be retrieved from the generative vector without collapsing into triviality. Across each stage, neither platform produced iconic Bowie, no Ziggy lightning bolt, no Aladdin Sane flash, no Thin White Duke pallor, even though some of the prompts explicitly mentioned Bowie by name.

The two platforms navigated the Artist/Minotaur’s statistical valley along divergent paths. Gemini maintained the beast-figure throughout, evolving from the sculptor, through the crime-scene documenter, to the exhausted, mask-wearing painter. The Minotaur, in Gemini’s rendering, is a costume the artist puts on and takes off, which resonates with Bowie’s own method of becoming the character, then killing it when it threatens to consume you.

Midjourney took a different trajectory. The beast emerged, receded into the human, then returned as something monstrous and autonomous. In the final image, the artist sits with the creation that has grown beyond them. The Minotaur here is not a mask but a consequence of what happens when the ritual succeeds too well.

Both outputs are reasonably described as nontrivial. Neither reproduces archived Bowie imagery nor generates generic mythology. Instead, they transform the concept of the Artist/Minotaur through the generative vector’s own logic. Different probability paths through the same weighted terrain, producing new configurations that nonetheless feel connected to their source.

The experiment suggests a strategy for navigating statistical valleys: concept before image. By prompting for what the Artist/Minotaur means rather than what it looks like, we bypassed the heavily weighted peaks of iconic Bowie. The archival context introduced in Stage 4 enriched rather than flattened the outputs precisely because the conceptual frame was already established.

This is curatorial labour in the generative vector. The human role is not simply to run prompts and accept outputs, but to navigate the stratified landscape of latent space—to find paths around the statistical peaks toward the sparse regions where rarer material persists.

The Generative Vector and Non-Human Persona

What does this mean for the posthumous non-human online persona? The experiment offers cautious optimism. The iconic Bowie (Ziggy, Aladdin Sane, the Thin White Duke) will always exert gravitational pull in the generative vector. These figures are statistical peaks, heavily weighted through decades of circulation in the archival vector. But they are not the only Bowie available for actualisation.

The marginal Bowies, the Minotaur painter, the Verbasizer experimenter, the Nathan Adler narrator, all persist as potential. Their retrieval requires what Deleuze and Guattari might call a minor use of the generative tools: prompting strategies that stammer the system away from its default outputs and toward the valleys rather than the peaks. The infinite Bowie need not collapse into greatest-hits repetition if fans and users engage as curators rather than consumers.

But this optimism is provisional. The experiment involved careful, multi-stage prompting with explicit conceptual framing. Most engagement with generative media is not so deliberate. The recursive loop, in which generated outputs feed back into the training data, may progressively flatten the landscape, eroding valleys as the peaks grow ever more dominant. Whether the Minotaur will remain retrievable, or whether the Infinite Bowie will eventually contain only Ziggy and his shadows, is a question for the third vector: the recursive loop awaits.

Next post – Pushing into Recursive Vector.

Leave a comment